by Neha Dixit

Geeta’s wedding has been fixed for November. The only thing that she has not done to forestall the calamity is run away with Saurabh. But now she is contemplating taking that ultimate step.

Geeta’s wedding has been fixed for November. The only thing that she has not done to forestall the calamity is run away with Saurabh. But now she is contemplating taking that ultimate step.

She has lied to her parents, telling them that she is doing a stitching course in Gurgaon when she is not. It is how she manages to still meet Saurabh every day.

Geeta walks into the café, exactly at eight in the morning. It is familiar ground. She started working in the café three years back. That is when she met him.

Today, it is empty and Saurabh is still wiping the speckled floor with a rag. She sits at the end of the chair on a table at the far left of the café. I sit next to her. Saurabh leaves the rag on the floor, walks to the dusty counter and brings back to two cups of coffee for us.

“She is my didi. She wanted to come with me today,” she tells him.

Saurabh looks at me for a second, smiles and goes back to cleaning the floor. He then starts wiping the counter.

****

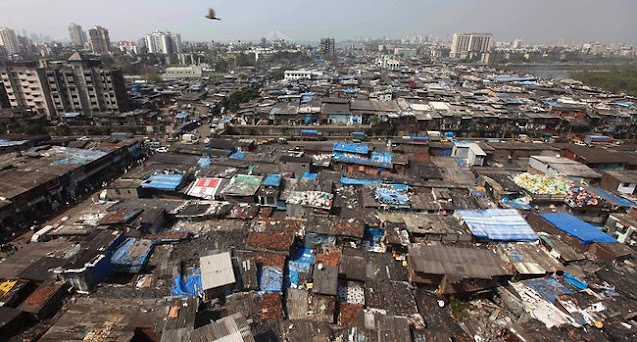

Geeta’s parents came to Delhi twenty years back from Darbhanga, a small town in Bihar. She was a year old and her elder sister was three. The younger brother and a sister were born later. After living in Sangam Vihar for a few years, they moved to Dairy camp in Vasant Kunj, a big slum populated with lots of family’s acquaintances from back home.

Geeta’s parents came to Delhi twenty years back from Darbhanga, a small town in Bihar. She was a year old and her elder sister was three. The younger brother and a sister were born later. After living in Sangam Vihar for a few years, they moved to Dairy camp in Vasant Kunj, a big slum populated with lots of family’s acquaintances from back home.

Fifty two percent of Delhi’s population lives in slums without basic amenities, often cheek by jowl with affluent colonies which hire their services. Geeta’s father got a job at a dry cleaner’s shop. Her mother started working as a domestic help in the nearby flats.

So when her elder sister wanted to learn stitching and her father objected, the mother secretly paid the fees and sent her out of the house. The elder sister now stitches blouses, petticoats and salwar kameez part time, enough to take care of medical expenses of her repeated miscarriages. She was married off when she was 18 because the father insisted.

When Geeta turned 18, and completed her school education, she announced her desire to work. The father blamed it on the bad influence of the pastor on Sumitra, her mother.

Sumitra had converted to Christianity eight years back. She was bed ridden for almost a year with an undiagnosed disease and thousands of rupees spent on the treatment. She had lost all her jobs at various houses because of the frequent illness. Then, one day Pastorji came to her house, prayed to God and gave her a glass of water to drink. She was cured within a week. It is then she gave up on Hindu pooja-path and started attending the Pastor’s prayer meetings.

Geeta’s father was grateful to the Pastor that his wife was saved but did not like the monthly prayers at his place when several women, cured by the Pastor, would come to his house to do Christian prayers. While his wife and daughters were allowed to participate, he and his son would sit outside the house to make it clear that they were still Hindus. All families in the slum, whose women have converted to Christianity, experiment with this democracy in religious beliefs. But the lines are still blurred.

Pastorji told Sumitra that caste system is immoral but the father still insisted that all marriages in the family should be arranged within his ‘Dhobi’ caste. After all, it is he who has to think of the ‘Samaj.’ Sumitra would often retort that there was no sign of the ‘Samaj’ from Darbhanga when there was no money for food and medicines. When Geeta found a job in a café in Gurgaon, it was Sumitra who supported her.

****

Saurabh moves behind the counter, arranging and rearranging the many items, while Geeta, her elbows on the table, looks steadfastly out the wide café window at the street. She wears a downhearted expression though she occasionally turns to look at me and smile.

Geeta and Saurabh started seeing each other a year after Geeta started working at the cafe.

“I had a fight with the owner. He was paying me Rs 6,000 a month. When he denied me a raise the next year, I yelled at him, ‘Sir, you sell 100 coffees for Rs 300 each every day and cannot give me a 1000 rupees raise.’ Everyone sitting in the café turned around and looked at me. The café owner laughed out loud but I froze,” she recalls.

“I had a fight with the owner. He was paying me Rs 6,000 a month. When he denied me a raise the next year, I yelled at him, ‘Sir, you sell 100 coffees for Rs 300 each every day and cannot give me a 1000 rupees raise.’ Everyone sitting in the café turned around and looked at me. The café owner laughed out loud but I froze,” she recalls.

The café owner is young and according to Geeta ‘good natured.’ He’s known Geeta since she was a child. Sumitra had worked in his house for ten years and as a domestic help. “The café owner recently got married. Love marriage,” she says wistfully.

Saurabh had liked Geeta’s guts and that’s when they got talking more than usual. “We would wonder that who are these school kids who spend Rs 1000 a day, come in big cars and then study in the café?” she says.

Saurabh, who also lived in the same slum as Geeta, had bought a bike and would often drop her midway home and then she would take a bus back.

“I studied in a government school and did not understand English initially. He had gone to a public school and helped me learn a few sentences so that I can take orders in the café. It was him who took me to Big Bazaar to buy clothes. It used to scare me before that. And you see this cellphone,” she points at her Android smartphone, “he bought me this to be able to use Whatsapp and listen to all the songs he wanted me to.”

After two years of togetherness, they were convinced that they wanted to marry. Geeta was sure that Sumitra would agree. After all, it was her mother who had advised Geeta that her future husband should be educated, and not from a village. Sumitra did not object to Saurabh’s caste. Her problem was that no one from Saurabh’s family followed the pastor. “The pastor had told her that girls who start attending prayers should not go back to pooja-path. Otherwise, everything good reverses and becomes destructive for the family,” she recounts.

Geeta was forced to leave her job. Her modest stab at independence squelched in its infancy.

****

“Young girls from urban poor sections show a change in their attitude towards the kind of lives they envisage for themselves. The parents or the community fear that their independent decisions will lead to more rebellion and bring down the patriarchal structures,” says Rakesh Sengar, an activist with Bachpan Bachao Andolan. Without any support systems or protection from the state, the young women remain trapped within confines of their parents expectations.

“Young girls from urban poor sections show a change in their attitude towards the kind of lives they envisage for themselves. The parents or the community fear that their independent decisions will lead to more rebellion and bring down the patriarchal structures,” says Rakesh Sengar, an activist with Bachpan Bachao Andolan. Without any support systems or protection from the state, the young women remain trapped within confines of their parents expectations.

He points out that the exponential rise in the urban poor is growing in proportion to their aspirations which remain unaddressed.

As we talk, Saurabh puts the chairs stacked on top of the tables back in position to ready the cafe. He does not look at us even when he’s next to us.

As we talk, Saurabh puts the chairs stacked on top of the tables back in position to ready the cafe. He does not look at us even when he’s next to us.

“He understands me the best. His mother has also worked as a maid for so many years. He cannot judge me for that. And he knows that I don’t want to end up working in other people’s houses either after marriage,” Geeta tells me.

“My sister’s husband told her that he can take care of the house after marriage but see? Now she has picked up work to make ends meet. Both partners have to work for a better life. More importantly when they don’t want to spend their lives in a slum,” she said.

Rishikant, an activist who runs Shakti Vahini, which works on issues of trafficking and issues young women face in metropolitan cities says the aspirations of young women are not respected in the current social structures. “When young girls get basic education and exposure in metropolitan cities, they aspire for an identity. Jobs that are different from their mother’s generation open a new window to aspire for independence. However, the choices they make are met with barriers and lack of understanding. The class divide makes harder their struggle to live the life they wish to lead,” he says.

The calm in the café is disturbed when Saurabh opens the last shutter over the wide window. The café is about to open.

“He is upset with me that I am not ready to elope with him. I have to think about my mother and sister. He does not answer my phone but he still makes me coffee every day,” she tells me, explaining their silent daily ritual.

“He is upset with me that I am not ready to elope with him. I have to think about my mother and sister. He does not answer my phone but he still makes me coffee every day,” she tells me, explaining their silent daily ritual.

According to National Crime Record Bureau, in 2014, Delhi witnessed the highest number of suicides over ‘love affairs’ among 55 cities. As many as 63 people, 38 men and 25 women, committed suicide over lover affairs.

“What will you do now?” I ask, as she signals me to get up.

“I still have time till November,” she says and walks out the door.

Saurabh picks up the empty coffee cups and goes back to the counter.

(Some names have been changed)

Published by FirstPost on August 13, 2015

Link: http://m.firstpost.com/specials/love-liberty-pursuit-happiness-delhi-slum-2385708.html