After recent arrests, hundreds of Rohingya refugees have started fleeing relief camps in Jammu. Here are the stories of three women who lived in these camps.

Neha Dixit

On March 7 this year, close to 160 Rohingya refugees living in Jammu were detained in a sub-jail. According to officials, they were sent to a “holding centre” under the Foreigners Act and did not hold valid travel documents.

India does not have any legislation recognising refugees, but the country adheres to the principle of non-refoulement (not sending refugees to a place where they face danger) as part of the customary international law. Some of them have cards issued by the UN High Commission for Refugees acknowledging their status as refugees.

In the last decade, in an effort to “purify” Myanmar, Buddhist supremacists have been committing rape, arson, murder and land confiscation on a massive scale against Rohingya people. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya struggle to survive. They are denied freedom of movement, marriage, jobs and schooling. At least an equal number of refugees have fled to an unknown fate. Unknown numbers of people have drowned or been captured by traffickers to toil as slaves. Some found second-class residency in Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh and India, living at a risk of another expulsion. Till date, an estimated 140,000 Rohingya people have been displaced from Myanmar.

Different socio-economic factors that have brought close to 36,000 Rohingya Muslims to India. Over 6,523 Rohingya refugees live in 39 camps that are located across Jammu.

This is not the first time they are facing Islamophobia, the risk of expulsion and life threats in Jammu. In April 2017, Rakesh Gupta, the president of Jammu Chambers of Commerce and Industries (CCI), had warned the state government that if it does not deport the 6,000 Rohingya living in Jammu, he will launch an “identify and kill movement against such criminals”. Gupta called this demand a part of the Chamber’s “corporate social responsibility”. The same year, I met several Rohingya women in relief camps in Jammu.

After the recent arrests, hundreds of Rohingya refugees have started fleeing these relief camps, where they had been staying for almost a decade. Social media has been flooded with pictures and videos of Rohingya refugees leaving their camps and walking on the highways along with their belongings.

In these pictures you will also find Mumtaz, Mariam and Bilkis, who I met. These are their stories.

I. Black magic

“Mumtaz Begum practices black magic. Else which kind of girl survives a dead family, a runaway husband and still paint her nails red,” warns Mehrunissa, a 60-year-old woman from Kariyani pond camp of Rohingya settlement in Jammu, a north Indian district with a large Rohingya refugee settlement.

Mumtaz Begum is 22. The entrance to her shanty is adorned with sequin embroidery patches that sparkle in the winter sunshine. She had fled Maungdaw in Myanmar along with her neighbours after her village was attacked by the Buddhist mobs in 2013. “The sight of my parents and younger siblings chopped to death does not fade away from the mind easily,” she says.

The neighbours, Shahida and her husband Younis, both in their 60s, were the only familiar faces she could trace after losing her family. They first crossed over to Bangladesh and then came to Jammu via Kolkata in India. “They were kind and sheltered me throughout. There are not many takers for an orphan, unmarried girl for this sort of help,” she says.

That’s where she was introduced to Mohammed Aarif, 42, a man 20 years her senior. Aarif too had lost his family like Mumtaz, except that he did not have the assurance that Mumtaz had, that they were dead. He worked as a farmer in Buthidaung town of Rakhine State in Myanmar. Then there was a spate of violence in April 2011 where his house and crops were set to fire. This was the second time in two years. His brother had already shifted with his family to Cox Bazaar in Bangladesh, a year before when the sectarian violence against Rohingya Muslims had taken full swing.

Nagma, his wife and his three sons packed whatever was left at home and joined a set of 300 people who were leaving Arakan to go to Bangladesh, with a plan to come back once the conflict cools down. They walked for nine days to reach the Myanmar-Bangladesh border on a night in May 2011. As they reached, there was a small explosion and the ground beneath Nagma’s feet moved. It left a gaping wound in her right leg. It was a suspected landmine that had been allegedly put in by the inter-agency border control force called Nasaka to prevent the Rohingya refugees from returning to Bangladesh.

She bled profusely as the shrapnel had torn her flesh apart. There were long queues and a waitlist to let the refugees in through the border. They were told that they had to wait for another ten hours before they would be allowed entry to Bangladesh and then access the makeshift clinic to treat Nagma. Aarif asked his sons to wait on her as he went looking for a way to speed up the process. When he returned an hour later, most people from the spot had fled after a rumour that the Burmese military was moving towards the border to attack them. That was the last time Aarif saw them.

He looked for them in Cox Bazaar for an entire year before someone told them that his family is in Jammu. Next week, he crossed over to India, took a train from Kolkata to Jammu, and reached the Narwal camp near Kariyani talab in June 2012. Shahida and Younis, the neighbours who had given refuge to Mumtaz, were Aarif’s maternal uncle and aunt.

They helped him to look for Nagma and the boys all over. They even made trips to Hyderabad and Delhi, where there is a large Rohingya settlement, to look for them. But they were nowhere to be found.

In 2013, when the next round of Rohingya refugees landed in Jammu, he heard from one of the families that Nagma and the boys were killed by the Burmese military. Aarif sunk into depression for several months. To shake him out of it, the patriarchs of the camp decided to get him married off to Mumtaz. “This is an efficient way of getting people to start a new life,” says Yousuf, a self-appointed community leader in the camp. “Initially, Aarif was unwilling but we convinced him. Both of them were alone. So that was the correct thing to do. Also, an unmarried girl should be gotten rid of as soon as possible,” he says.

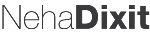

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

Aarif and Mumtaz got married in September 2014 and set up a new shanty in the settlement. “I constructed it bit by bit, just like the ones in my village in Maungdaw. Just like my mother made back home,” says Mumtaz. She set up tall bamboo poles to raise the height, with bamboo partition walls. The walls were three-layered – a bamboo mat, tarpaulin and blankets. There was also an attic, unlike the Indian shanties. “Attics help during waterlogging,” she says.

A new life seemed to have begun. Aarif started getting regular work as a daily-wage labourer with a local contractor who was laying broadband cables all over Jammu city. Mumtaz transformed from an emaciated, pale, short girl with matted hair to a plump, glowing woman with new clothes and trimmed, neat hair. She no more doubled up as the community babysitter or children’s barber to survive on leftover food and castaway clothes. Her time was now either used up in fixing her house or practicing brocade or sequin embroidery on her clothes, hair bands, burqas and even the wall hangings. She was no more dependent on her neighbours.

Meanwhile, Shahida and Younis traced their elder son to a Rohingya settlement in the Mewat district of Haryana, 700 km from Jammu, and moved there.

“He was a reserved, quiet man. She was talkative, extroverted and social. She forgot that she was now a married woman and could not go around galloping like pampered teenagers,” says Afsana, her 40-year-old neighbour, disapprovingly.

Rubaiya, another neighbour from the camp interrupts, “Poor girl, she had found someone of her own after three years. And Aarif never stopped her from mingling.”

“She kept arguing with Aarif over silly things. Like why does he not eat the lunch she packs for him? Why does he not talk to her enough? Why does he talk about Nagma and his sons so much? And why does he not buy a smartphone to play music and films?” adds Afsana. “It is a sin for a woman to question and badger their husbands. With a big mouth and no hesitation even when she had lost her whole family.”

Then, one day, Aarif did buy a mobile phone that played music and had internet. He got obsessed with WhatsApp and managed to connect with his displaced family and friends all over Asia. He found his elder brother in Malaysia, an uncle in UAE, one nephew in Delhi through several WhatsApp groups. “That is how a lot of Rohingya people continue to find their lost ones,” says Yousuf.

A year later, in September 2017, he found a message in one of the groups. “Mohd Salim, son of Mohd Aarif from Buthidaung in Myanmar looking for him. Contact on this number.” Aarif immediately called on the number.

“He spoke to his wife and the elder son, Salim, and found out that they were in Kutupalong refugee camp in Ukhia in Cox Bazaar, Bangladesh,” says Yousuf.

Two days later, Aarif had tea just like any regular morning; Mumtaz packed his lunch like she did every day. He gave Mumtaz a new smartphone and told her that he had found his lost family in a very matter-of-fact tone. Before Mumtaz could ask any question, he left for work. He did not come back that evening, the next evening or the evening after that. It has been four months.

Yousuf says, “Who will say that she has been deserted by her husband? Look at that sparkling sequence burqa. No grief on her face at all. This is why Aarif ran away.”

Mumtaz has found out through WhatsApp on her blue smartphone that Aarif has reunited with his family. “I can’t reach his phone. I can’t even reach his son’s phone. I don’t even have the money to go there,” she points to a picture of Aarif and his family in Bangladesh.

The other day, Yousuf told Mumtaz that Aarif told him that he plans to settle in Bangladesh. “He has no reason to come. He doesn’t even have children with Mumtaz. She is cursed, that is why no one stays with her, family, husband, no one,” he says.

Mumtaz thinks, in retrospect, that it is good that she does not have children or she would have had to explain their abandonment. “Children cannot be reproduced alone. Things also need to be done by the husband too,” she says.

Mumtaz now embroiders from home for a local boutique and earns her own living, unlike other single women who continue to work as babysitters for the community’s children for food and shelter.

“I always knew that she practiced black magic. With those needles and threads. How else can a young, single girl live without the community’s help?”

II. This camp, that camp

“I know all about groundnuts, betelnut, coconut. We used to grow them on our farms back home. But walnut, I saw it for the first time only in India,” says Mariam Bibi, a 16-year-old worker, as she pauses to think. She continues, “Actually, we don’t get them back home, in Burma. Even the potatoes, watermelons, mangoes and guavas we get there are not like the Indian ones. They are smaller, sweeter and much better quality,” she says.

Ashiya, a 45-year-old worker in a yellow thami (a traditional Burmese skirt) and blue scarf, intervenes, “Till when are you going to keep comparing the potatoes and tomatoes from Burma and India? Get used to them. We are not going back anytime soon.”

Mariam smiles and continues to break walnuts with a flat stone, sitting on the floor and extracting the kernels with a screwdriver.

She works in a walnut ‘factory’ in the Kariyali pond camp in Jammu. She moved here with her mother, three younger sisters, and two elder brothers from Maungdaw in Myanmar in 2013.

The ‘factory’ is owned by Veeru, a local feudal landlord. He is 50, tall and large, and his hair and beard are dyed in henna. Veeru has set up numerous small tin shed ‘factories’ in the camp where women and children extract walnut kernels. The big tin sheds are lined with gunny bags full of walnuts in one half, and the other half has workers queued up on the bare, cold floor to break the walnuts.

For every one kg of the walnut kernel they extract, the workers are paid Rs 10 ($0.15). Mariam is the most efficient and fastest extractor, and manages to make Rs 80 ($1.2) over 12 hours of work. Veeru also owns the land on which this Rohingya ghetto near Kariyani talab in Jammu exists. There are 800 families – 3,000 people – here. The rent per shanty is Rs 1,500 ($24), plus Rs 1,000($16) for electricity and Rs 300 ($5) for water, each month. Mariam also lives here and makes roughly Rs 2,000 per month ($32).

The workers, mostly women, assemble at 6 am and extract the kernels till 6 pm. Young girls like Mariam sometimes work for one or two extra hours if they have younger sisters who can do the housework and the cooking on their behalf.

It is mandatory for at least one woman from each household in the settlement to work in this factory. The three women who refused because of back problems and the other seven who started working in walnut ‘factories’ outside because they were getting paid Rs 16 ($0.25) per kg of extracted walnut kernels have been shunted out of the ghetto. “He owns the land. He decides who gets to stay here,” says Mariam.

Mariam’s father, Junaid, was a singer and a tabla player. “Have you seen a tabla? It is a set of two drums with a leather membrane over it. Like this,” Ayesha, Mariam’s ten-year-old sister, explains by putting a polybag membrane over the recycled paint bucket Mariam was using to store the walnut kernels. The bucket topples and the kernels spill on the ground. Tabla is a common classical musical instrument in the Indian subcontinent.

Mariam scolds Ayesha, “That’s why I asked you to not bunk school. Now open your copy and finish the homework.” Young children like Ayesha from the settlement go to an NGO-run school in the vicinity. There are a couple of such schools in the neighbourhood. Mariam couldn’t complete school because the Burmese government wouldn’t let Rohingya children get higher education in schools in Rakhine State.

Ayesha replies, “But it is so cold. My hands don’t move in the school.”

Mariam starts talking, “We have three seasons in Burma – winter, summer and monsoon – three months each. Not like India with extreme winters and summers.”

Ashiya yells, “Again! Why do you keep talking about things that don’t matter, don’t exist in our lives any longer?”

One day, in January 2012 in Maungdaw, when it was as cold as this day in Jammu, Junaid was out for a musical performance at a wedding. That is when he was picked up by the military. They took him to the hills as a porter to carry arms and ammunition. Forced labour by the military in Myanmar is a common practice. In 2005, the International Labour Organisation governing body stated that “…no adequate moves have been taken by the Burmese Military Regime (the ‘Government’ of Myanmar) to reduce forced labor in Burma/Myanmar.”

Mariam’s family looked for her father all over, “but whoever is once taken away as a porter by the Nepalis never comes back”, she says with a straight face as Ayesha listens intently. Nepali is a slang used for Burmese by Rohingya Muslims owing to their Mongoloid features.

It is the same year when a series of conflicts between Rohingya Muslims and ethnic Rakhines in the Rakhine State of Myanmar was triggered. Riots were instigated by insinuations that the Buddhist Rakhines will soon become a minority in the state. This alluded to the stereotype that Muslims produce more kids. On May 28, 2012, news spread that three Rohingya Muslim men had raped a Buddhist woman in Rakhine State. As part of a major backlash against the Rohingya, houses in 14 villages were burnt down that night itself. In the spate of violence over the next few months, close to 2,500 houses were destroyed and over 30,000 people were displaced. The homeless, affected Rohingya were taken to the 37 IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) camps set up by the Myanmarese government.

Mariam and her family had to stay in one such camp in Maungdaw township.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

The IDP camp was meant to protect the displaced Rohingya Muslims but the army instead converted them into jails. “There was no drinking water, food or doctor,” says Humaira, Ayesha’s 12-year-old daughter who was helping her break extra walnuts for the day. The inhabitants of the camp were completely cut off from all livelihood options. “We were not even allowed to go out and do some farming or fishing, or collect firewood to cook. We were starving.”

It is estimated that about 140,000 Rohingya in Burma still remain confined in IDP camps. According to a report by the World Food Program, Maungdaw is one of the worst locations in Burma in terms of food security. A study found that close to two-thirds of households are unable to acquire an adequate amount of food to sustain their diet.

Unable to see the family starving, one day in October 2012, Haroon, Ayesha’s husband, took the risk. He was a fisherman and he escaped to earn some money. “His dead body was thrown outside the camp the next day. He was hogtied with a plastic strip with a gunshot on the forehead,” says Ayesha, also with a straight face.

There is silence for half a minute which is broken by Mariam, “It was done to send us a message. Even the restrictions on us were deliberate. To make us leave the country.”

According to a report by Human Rights Watch, “Many Muslim IDPs have been living in overcrowded tent camps, others in “semi-permanent” structures, and some have had no shelter or basic aid at all, in full knowledge of the Burmese authorities. Meanwhile, the relatively few sites populated by displaced Arakanese have been well provided for by local and national government programs, and are supported by national TV and radio fundraising drives that secure donations from Burmese society only for displaced Arakanese.”

Ayesha says, “Buddhists are free but Muslims are not.” After that, 12 families including Mariam and Ayesha’s collected some money to pay a middleman to ensure a safe passage to Jammu. It took them over two months via Bangladesh to reach here in February 2013.

Mariam butts in, “I learned Hindi in flat two weeks. It is in some ways similar to our language. And we also have different dialects. Just like in India.”

“We didn’t know the language, we are very different from the Muslims here but our biggest achievement in the last five years here is that we have managed to stay alive,” says Ayesha.

Veeru walks in and says in a roaring voice, “Will you women work also or keep talking?”

The women and young girls nod and continue to work. He walks out.

“So which camp is better? He uses force and pays you less,” I ask.

“The Indians rant too much but at least no one has yet attacked us physically, unlike Myanmar,” says Mariam with a smile.

Ayesha says, “Don’t say bad things about Indians. You should be sent back to Burma.”

Mariam replies, “Don’t tell me that you don’t crave the curry with bamboo and prawns which you haven’t eaten in six years. I know you want to go back home. See, see. Your mouth is watering.”

Ayesha lifts her head with a beaming smile on her lips. Everyone bursts into laughter.

III. Companion

When Bilkis Jaan, 60, fled from her village, Bohmu Para in Maungdaw district, in June 2013, Ghona, her 12-year-old, brown- and black-furred bitch, cried to death.

Ghona was her constant companion for ten years. She was a few-months-old puppy when she adopted Bilkis. Rehmat Ali, Bilkis’s 45-year-old husband, had just passed away. He was a skilled boatsman and ferried people in the Kaladan River. It is the fifth-largest river in the world to remain unfragmented by dams in its catchment. Over the years, the water got polluted, with India and Myanmar trying to connect seaports of both the countries through the Kaladan Multi Nodal Transit Transport System. This caused an infection in his legs, amputation and death within a few months of that.

Bilkis had two daughters, Safiyah and Shagufta. To raise them, she took up work as a farm labourer. That’s where Ghona found her. “The owners grew peas and chillis, better quality than the ones you get in Jammu. Ghona would stay with me like she was a part of my body,” she says – dig when she would plough, cover the pit with mud when Bilkis would try to fill it.

The next year, Essar, an Indian oil company, started exploring natural gas options in Sittwe and Maungdaw area in the state. The area falls under what is called L Block, an oil exploration circle. As part of an agreement signed in 2005, Essar along with the state-run Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise was to do drilling test wells in the area. Over two million acres have been seized from minorities in Burma for such projects by India and China. The farm patch on which Bilkis was employed was also taken away.

She then took up a job at a butcher shop. At the end of each day, she was given a few pieces of meat and some money as a monthly allowance. Ghona would follow her there too.

“Unlike Indians, we cannot survive with just vegetables. We need meat every day. Even the fish that you get in India is dead. We used to catch fish fresh from the pond and the river and cook it. It used to taste so much better. Ghona would sit quietly next to me when I would catch fish in return for a fresh fish at the end of the exercise,” she says. She worked at the shop for five years.

In 2011, the butcher shop was set on fire on accusations of selling pork by Kaman Muslims, an ethnic Muslim group recognised by the Burmese government as one of the seven ethnic groups of Rakhine, who are acknowledged as Burmese citizens and hold national identity cards. Consuming pork is prohibited in Islam. After the onslaught against the Rohingya Muslims started in Myanmar, several Kaman Muslims have also been targeted by Buddhists for sharing the same faith. “This led to conflict, insecurity and a competition to prove who were better Muslims,” says Bilkis.

While she was still doing odd jobs to make ends meet, within a year, in 2012, a mob of Buddhists from Arakan along with the Burmese military attacked her village. They entered the house and caught hold of 15-year-old Safiyah. “They did the same as what was done to several of her Rohingya sisters. We were in the same room when it happened. I asked her not to resist as two men, one after another, thrust themselves over her. Tears flowed from her eyes as she stared at me. They would have done the same to my other daughter had I tried to save Safiyah. Ghona kept barking, tied in one corner of the same room. The army guys kept asking me to shut Ghonu up or they will shoot her,” Bilkis recounts in a matter-of-fact tone.

Rohingya have little access to healthcare in Myanmar. In a vitiated environment, getting Safiyah treated medically was impossible. Her private parts bled profusely for days and she succumbed to her injuries three days later.

A humanitarian aid agency came to the village the next day and took away all the Rohingya to a camp. “They refused to allow Ghona in the truck. She watched as we got on to it. Barked and barked and then followed us for a full one hour before the swampy mud patch slowed her down while the truck raced away. I lost my body part of 12 years,” says a teary-eyed Bilkis.

Bilkis and Shagufta came to Jammu three months later to stay with relatives, where 17-year-old Shagufta was married off to her first cousin, Saif.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

In September 2017, a carcass of a dead cow was found next to their shanty. Twelve people along with Saif were picked up by the cops at the Channi Himmat police station in South Jammu. Members of the BJP, a Hindu nationalist political party, accused the detained of consuming beef and hurting religious sentiment.

“What do people get by fighting over meat. Pork in Myanmar and beef in India when millions have already been killed over religion,” she says.

Bilkis now works in a butcher shop next to her camp where they supply fresh fish, prawns, and mutton to the four Rohingya settlements in the vicinity. Her new companion is a ginger cat named Jhontu, who loves fish.

Neha Dixit is an independent journalist based out of New Delhi. She covers politics, gender and social justice in South Asia.

Published by The Wire on March 25, 2021

Original link: https://thewire.in/rights/rohingya-refugee-women-jammu